Turmeric pellets reduce coat, sweating of horse with Cushing’s disease

Kurt’s hair is dry in 6-degree weather on Feb. 7, 2021.

Post reviewed on Nov. 26, 2022

Turmeric pellets may be a relatively cheap and easy-to-use treatment if your horse is dealing with Cushing’s disease and related symptoms, such as sweating.

I cannot say turmeric pellets improve laminitis issues in the hoof.

But turmeric pellets have reduced my gelding’s sweating during the winter, including when the temperature drops to zero, and made him much more comfortable, improving his quality of life dramatically.

Turmeric, an herb belonging to the ginger family, is the major source of curcumin, a polyphenol (micronutrient) that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, according to many studies.

However, a major problem with curcumin is its poor bioavailability.

I initially started trying to give my horses turmeric in powdered form in December 2014, because of its chelation activity. It removes iron from the cells of the body and lowers ferritin levels, according to many sources, including the Hemochromatosis Help website. If my horses indeed suffer from iron overload, as I’ve suspected for years, the turmeric should help.

Adding turmeric powder lasted only a few weeks each time I tried it because the horses wound up colicking. I assumed that the turmeric, along with the horses’ on and off again use of bute, was making ulcers flare up.

During the three winters prior to the 2019-2020 winter, Kurt, my last horse and a longtime sufferer of laminitis, developed a huge, curly coat and sweated all winter, even when the temperature dropped below zero. He didn’t mind his wet coat icing over like everything else in sub-freezing temperatures, but I panicked through every deep cold snap.

In the fall of 2019, I noticed that SmartPak was selling turmeric in pellet form. I have no affiliation with SmartPak and receive no compensation or discount for saying the brand name.

Kurt started on the supplement Oct. 31, 2019. Two months later, it was obvious the turmeric was having a positive effect on his coat. Sweating was greatly reduced on warm days and nonexistent on cold days.

That is still true.

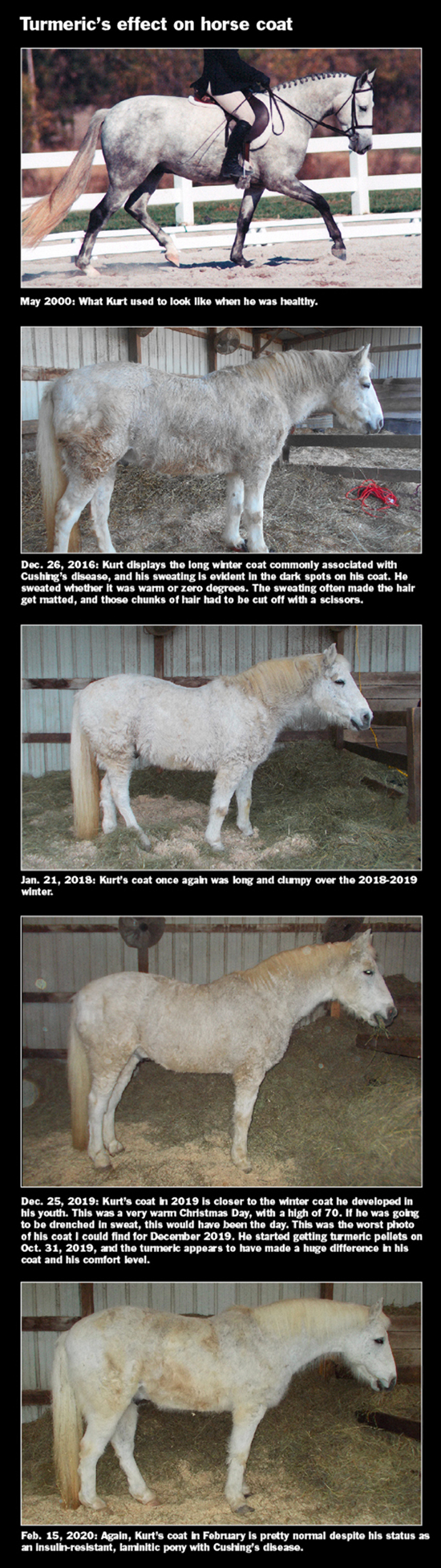

Here are photos of Kurt’s excessive coat in December 2016 and January 2019 and then his much lighter coat in December 2019, two months after he began the turmeric pellets, and in February 2020.

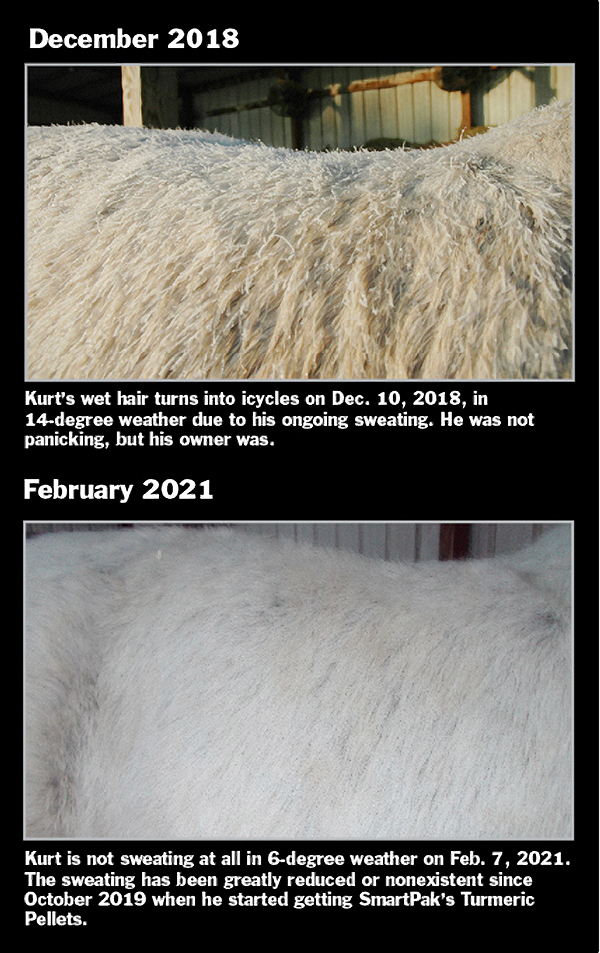

And here are pre- and post-turmeric-pellet photos of Kurt’s wet coat icing over on Dec. 10, 2018, a day with a morning low of 14 degrees, about the time when the photo was taken, and his coat completely dry in 6-degree weather on Feb. 7, 2021.

I give the turmeric pellets to Kurt separately after he eats his forage balancer. He likes the pellets more than his forage balancer and treats them like dessert. The dose is one scoop a day of 10,000 mg of turmeric. At least one study has used a higher amount.

I’ve tasted it and it tastes like someone dumped a spice rack in my mouth, but it’s not bad.

I don’t know why Kurt can ingest the pellet with no issues, while the powdered turmeric always led to a bouts of colic. Some studies suggest turmeric actually improves ulcers.

A study presented at the 2020 AAEP meeting by Michael St. Blanc, DVM, from Louisiana State University’s School of Veterinary Medicine, indicated that turmeric and devil’s claw fed together as a supplement to horses with pre-existing equine gastric ulcers did not worsen the ulcers, according to a report on thehorse.com. In fact all study horses — those fed the supplement and the control horses — saw their ulcers improve, likely due to the change in management of the horses once they were enrolled in the study, St. Blanc said. The turmeric dose in that study was 12,000 mg.

Cushing’s syndrome in horses is unique, according to VetFolio, in that it involves hyperplasia (an increase in the number of cells) in part of the pituitary gland rather than tumors in a different part of the gland — which occurs in humans.

Either condition can result in excessive production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

The excess ACTH causes the adrenal glands to make too much cortisol, which can lead to immune suppression and insulin resistance.

The website vetspecialists.com, a joint venture of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) and the American College of Veterinary Surgeons (ACVS), says equine Cushing’s disease, or pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID), is the most common endocrine disorder in horses, ponies, donkeys and mules. PPID most often affects older horses (teenage or older) but has been observed in some younger than 10 years of age.

Affected horses are prone to chronic infections such as sinusitis, dental disease, and sole abscesses.

The website lists these signs and symptom, and my gelding Kurt had them all (expect the abnormal heat cycles in mares):

1. Failure to shed hair fully each spring.

2. Long, wavy/curly hair.

3. Chronic infections.

4. Repeated laminitis episodes sometimes with associated hoof abscesses.

5. Excess or inappropriate sweating.

6. Increased water intake and urination.

7. Lethargy.

8. Loss of muscle mass, typically noticed over the back and hind quarters, as well as the “pot-bellied” appearance.

9. Infertility or abnormal heat cycles in mares.

There seems to be ample evidence in human studies that turmeric can help alleviate the cell activity behind Cushing’s disease. I am not finding a study in horses that examined curcumin’s effect on the pituitary gland or Cushing’s symptoms.

Authors of a German study in humans and rodents said their research “demonstrated for the first time that curcumin has anti-tumorigenic actions on rodent and human pituitary tumor cells in vitro and in vivo.” The research was published in 2009.

Given all the money I’ve thrown at laminitis supplements so far, the price of the turmeric pellets seemed more than reasonable.

I will keep Kurt on the turmeric pellets for the rest of his life, assuming they are available.