In my research on the history of laminitis, it was hard to overlook the recommendation in the fifth century by writer Publius Vegetius Renatus that a horse with hoof problems related to overfeeding barley — presumably laminitis — should be castrated.

Scientific research appears inconclusive on gender’s role in laminitis.

A study published in The Cornell Veterinarian journal in 1975 looked at a series of equine laminitis cases examined at the University of Missouri’s vet hospital from 1965 through 1971 and reported there were significantly fewer geldings among the affected horses.

A comprehensive review of studies published in November 2011 in The Veterinary Journal says study results were inconsistent in a number of categories. The review looked at published material from 1910 to 2010 and said there was good evidence of a link between chronic laminitis and increasing age. But, it said there were inconsistent results for many other risk factors including gender, breed and body weight.

Laminitis Help’s own unscientific survey online found the opposite to be true. Survey respondents reported the gender of their laminitis horses as follows:

Stallion: 6

Mare: 81

Gelding: 89.

I included that question in the survey because my veterinarian on my early cases, a laminitis specialist, said it seemed as if fewer geldings developed the disease. When I relayed that to my farrier, he said all his laminitic cases were female.

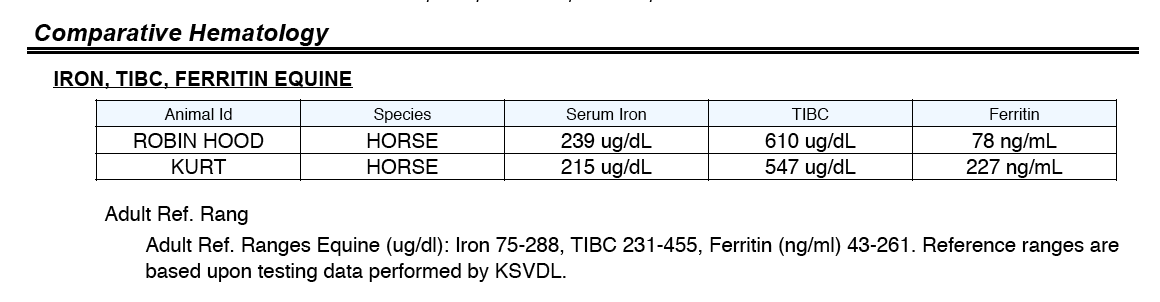

My horses participated in three studies total, the last two in 2007 and 2008, during which their blood was tested regularly, and the two geldings were closest to normal on insulin levels. Kurt was always in the normal range with the exception of one reading. The boys lived and ate in the same conditions as the girls. Whatever on this farm caused the consistent development of laminitis did eventually catch up with them. They both had elevated insulin in June 2011. But, it took much longer to get there.

I had been going through studies online for about a week looking for clues on geldings and laminitis, but a topic on “The Dr. Oz Show” on Jan. 13, 2011, moved me to draw a likely conclusion:

Insulin-resistant cases of laminitis may affect geldings less.

And since the insulin-resistant form of laminitis is the predominant form today, thanks to our horses getting fatter and fatter, perhaps geldings are developing it less.

Gender probably doesn’t play much of a role in grain overload or grass cases that change the microflora of the hindgut, leading to enzymatic changes in the feet. Nor does it probably play a big role in cases caused by standing on one foot too long to take the weight off the opposite foot.

But, once you get into insulin resistance, estrogen is a major player.

In the human world, women appear more likely to develop insulin resistance, according to medical experts. Some physicians suggest that all women are at risk, including Dr. Yehuda Handelsman, medical director of the Metabolic Institute of America.

“The Dr. Oz Show” talked about the link between fat, estrogen and insulin resistance. Estrogen causes the body to make more insulin, and more insulin creates belly fat. Increased fat cells make estrogen. Thus, women have a never-ending insulin-resistance cycle.

The Women to Women website, run by women physicians, says insulin resistance — also called syndrome X — is so pervasive today that the clinic evaluates almost every patient to determine the individual’s level of risk. The practice says most women are surprised to learn they either already have insulin resistance or early symptoms.

Note that men also have estrogen, which contributes to healthy functioning of the body and hormonal balance. They just have less of it, but that estrogen rises in time because testosterone is converted to estrogen as they age.

Life Extension, a nonprofit focused on anti-aging and optimal health, looked at endocrine factors in insulin resistance for both genders:

— As men age, they convert testosterone into estradiol, a form of estrogen. Their levels of estrogen and insulin increase, resulting in belly fat. Studies suggest that fat cells, particularly abdominal fat cells, convert testosterone to estradiol, and the more belly fat a man develops, the more testosterone is turned into estradiol. Thus, they have their own problematic cycle.

Perhaps geldings are less affected by rising insulin levels because they have less testosterone to convert to estrogen. If only I could find the study on that.

— In women, estrogen inhibits lipid (fat) oxidation for women when they reach puberty and, again, if they become pregnant, to store fat for functions related to child-bearing. This increases fat storage with no dietary changes. As “The Dr. Oz Show” pointed out, increased fat elevates estrogen, leading to elevated insulin and more fat.

— When women reach menopause, their progesterone and estrogen levels drop, with progesterone dropping at a faster rate, leading to an imbalance and “estrogen dominance,” again contributing to fat accumulation.

— In men and women, everyone over 35 sees lower levels of dehydroepiandrosterone, or DHEA , a steroid hormone whose drop may lead to weight gain.

— Beyond any medical conditions, aging causes cells to be more resistant to insulin. As cells refuse to accept insulin, insulin rises, resulting in more fat.

Lowering insulin resistance

Life Extension, which admittedly does sell products as part of its mission, says fiber can slow carbohydrate absorption. Particularly, taking in fiber before meals can reduce rapid absorption of simple carbohydrates and control blood sugar. It recommends a Canadian proprietary blend called PGX, or PolyGlycopleX, made of the purified soluble dietary fibers of glucomannan, xanthan and alginate plus mulberry concentrate.

I mention this brand because it’s the brand a medical expert recommended on this same “Dr. Oz Show,” and Oz admitted his wife uses it.

The expert was noted physician and author Mark Hyman, whose book and PBS special “The Blood Sugar Solution” (release date of March 2012) addresses insulin resistance and obesity.

Hyman said food more than drugs is the medicine of choice to treat diseases such as diabetes.

He says inflammation is the real enemy, because it comes first in the downward spiral, but inflammation can be turned around with diet.

Inflammation occurs when the body’s white blood cells try to fight off foreign substances. Sometimes, the body reacts when there is no real enemy. Chemicals in the white blood cells are released in the blood and tissue, leading to increased blood flow, possible redness and elevated temperature. The chemicals can cause damage to tissue.

Inflammation is usually temporary but, with an autoimmune cases, the body attacks its own cells and tissues and gets caught in a loop of chronic inflammation. Inflammation leads to insulin resistance.

Chris Kresser, practitioner of integrative medicine, says the modern lifestyle is to blame for inflammation and lists five specific causes. Horse owners familiar with laminitis triggers will see some familiar names:

• Dietary toxins (primarily refined wheat, fructose and industrial seed oils);

• Environmental toxins (chemicals like Bisphenol A, pesticides, phthalates, flame retardants, and heavy metals);

• Micronutrient deficiencies (especially magnesium and vitamin D);

• Chronic stress (emotional, psychological, physiological);

• Altered gut microbiota (caused by antibiotic use, poor diet, formula-feeding during infancy);

• Sedentary lifestyle

Hyman, the medical expert on “The Dr. Oz Show,” listed causes of inflammation as sugar and white flour and reactions to food such as gluten (wheat) and dairy; he says corn and processed soy also can be triggers.

Hyman says the supplement PGX is a super fiber from konjac root and seaweed that absorbs hundreds of times its weight in water and prevents spikes in insulin.

If PGX is such a miracle cure for insulin-related problems, I wonder if there’s a PGX for horses or if anyone has given PGX itself to horses?