Iron overload likely caused my horses’ laminitis

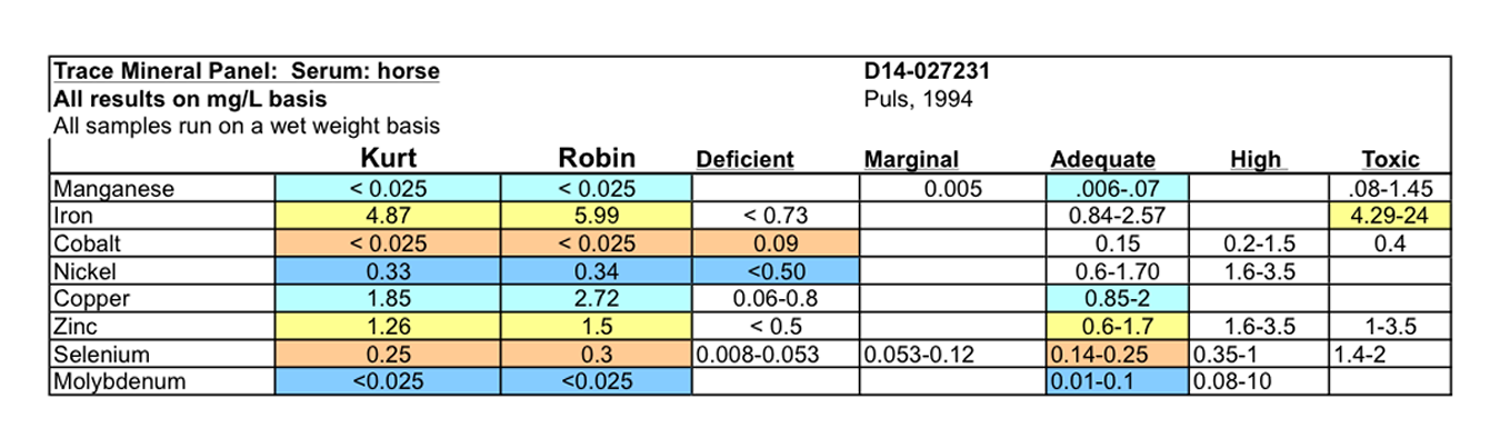

Toxicology test on horses’ iron level.

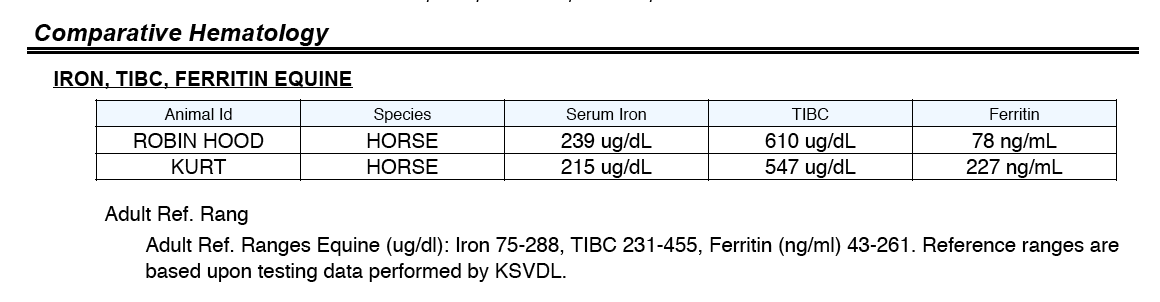

Hematology test on horses’ iron level.

Post reviewed Nov. 27, 2022

In “Clue” like fashion, I’m declaring the cause of my six horses’ laminitis over the last 18 years as an excess intake of iron from weeds, trace mineral blocks and well water, leading to insulin resistance and the insulin form of laminitis.

The insulin resistance and laminitis were exacerbated by me following veterinary guidance to restrict the horses’ hay, keep the horses on dry lots and prevent the horses from eating so-called “lush grass.” I now believe these moves were the exact opposite of what was needed to get the horses’ metabolism functioning properly.

In the game of “Clue,” I’d get immediate confirmation of whether my assertion is correct. Unfortunately, with the laminitis, I will receive no such feedback.

But a cascade of events led me to this conclusion.

In October 2014, I needed to have my leaking well fixed (the water pressure was down considerably, and a pond had formed to the west).

But I also wanted to have my horses’ iron levels tested at Kansas State University’s lab. I suspected iron as the cause of the horses’ laminitis for a decade but had no proof.

A previous iron test done through the local zoo did not provide useful results.

Several experts recommended KSU for these tests (I’m not making such a recommendation at the moment). I was hoping to do a three-test panel of serum iron, TIBC and ferritin (a hematology test) and a serum trace mineral panel (a toxicology test). I admit I didn’t know what I was doing. I wanted some data.

There wasn’t enough money to do the tests and fix the well.

The iron tests for my two living horses totaled $400, including my vet’s fees. I chose to do the tests and hope for the best with the well.

My vet didn’t provide this iron test as a regular service but agreed to draw the blood if I did the mailing.

I sent the package in a vet-provided cooled envelope by overnight shipping on a Thursday. KSU said shipping on Thursday was fine as long as the package arrived Friday morning. I don’t know what happened to the package after it got under way. I don’t know when it arrived or was tested, and all may have gone as planned.

I received results from KSU that suggested my horses had toxic levels of iron (see images at top).

A university vet who provided comments on the tests said the toxic level “could be indicative of artifactual hemolysis” within the submitted sample. In other words, the blood got too warm or tainted in transit.

I talked to a lab person by phone, and the blood was indeed considered compromised.

I personally believed the results were correct as far as the horses having too much iron but couldn’t be sure, and I couldn’t do the tests again due to the cost.

I had my own iron level tested through a company I found online, Lab Corp, for considerably less money, and my iron level was normal, making me think the iron theory had come up short.

My sister told me my iron results did not seem normal, given that all the women in my family were anemic. She said I likely was anemic, too, and was being affected by the iron in the water.

Meanwhile, also in 2014, veterinarian Frank Reilly, a leading advocate for laminitic horses, posted on his website the iron levels of common pasture weeds (scroll down to the tab titled “Equine Insulin Resistance High Iron“). The iron levels are really high. Excess iron can fuel insulin resistance. His site provides plenty of research on that, too.

I knew my horses had been eating more weeds than anything else in recent years because I had intentionally ignored the grass, thinking that less grass was better. The grass went away, and the horses ate the weeds.

I was suspicious of the well water having too much iron, since the water turns everything rust colored and has eaten through the bottom of all my aluminum tanks. But I still didn’t have proof there. A water test in 2005 showed nothing suspicious.

I did find out that the horses’ trace mineral blocks were 25 percent iron, and I threw those away in 2012.

In November 2014, I emailed Dr. Reilly, asking how one might reduce the iron level in horses through supplements. He spent his Thanksgiving holiday investigating this idea. He emailed back that curcumin and ginkgo could reduce the iron level, and he provided suggested amounts and where to buy it. Purebulk.com sells the curcumin (250 grams, $70 at the time — it’s gone up). Reilly suggested feeding 1/2 tablespoon a day. Starwest Botanicals sells ginkgo leaf cut and sifted (1 pound bag). Reilly suggested feeding 1 tablespoon in the morning and 1 tablespoon in the evening.

After giving the horses the two supplements for a few weeks, I stopped because my gelding Kurt was breaking out in drenching sweats as we entered yet another frigid winter. We eventually figured out the sweats were caused by thyroid powder (no longer given).

Also, a friend had sent me a camping filter for the well head to filter out iron, but I don’t use the well head during the winter due to the hose always being frozen. I carry buckets of hot water outside. So I didn’t put on the filter.

All these things nagged at me, but polar vortex winters tend to keep one busy.

I considered putting the horses back on the curcumin and ginkgo, but I wanted to do the iron tests again to see if the previous tests were correct. Does one want to chelate iron from a horse that doesn’t have excess iron?

There was no money to repeat the tests, and the situation with the well was becoming more of an emergency.

Everything came together in May 2015, when I finally had the well fixed, and a well company employee blurted out, “You must have an iron problem” when telling me how deep the well was. The casing is 350 feet deep (very deep) and collects iron all along the shaft, which gets transferred to the water as the water sloshes through, according to the well guy, an industry veteran.

The irony is not lost on me that fixing the well gave me more information than the iron tests.